The concept of the object itinerary (or the study of itinerant objects) emerged as a framework for understanding the complex lives and movements of material culture, following the seminar Things in Motion: Object Histories, Biographies, and Itineraries held in Santa Fe in May 2012 (Joyce and Gillespie 2015). This approach emphasizes the multifaceted circulation and transformations of things, moving beyond the notion of the object biography (or cultural biography of things), a theoretical model advanced by Igor Kopytoff (1986) that profoundly influenced anthropological and archaeological studies of material culture. While the object biography framework sought to illuminate the relationships between people and objects by tracing an object’s life history, its limitations prompted the adoption of the itinerary metaphor as a more dynamic alternative. Both concepts function as “narrative devices” (Joyce 2015, 23).

The Shift from Object Biography#

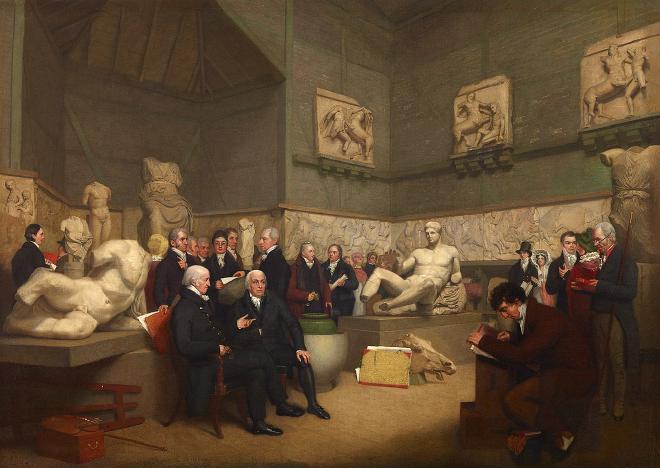

The rise of the object itinerary framework follows decades of influential work on material culture, beginning with the concept of the “social life of things” (Appadurai 1986) and Igor Kopytoff’s formulation of the object biography (1986), which explored how the meaning and value of things are transformed through circulation. Kopytoff suggested writing the life histories of things, following a model of birth, life, and death. However, the biography metaphor has been widely critiqued for several reasons. One major issue is linearity: the object biography approach tends to privilege a linear narrative (one with a clear beginning, middle, and end) and often struggles to account for the simultaneity of multiple, and sometimes contradictory, value systems. Kopytoff (1986) distinguished between commoditization (the process by which value is standardized, making an item exchangeable for other things) and singularization (the cultural process through which certain objects are kept unique and resistant to commoditization). He implied that these two processes are mutually exclusive — that something cannot be both singular and a commodity at the same time (Kopytoff 1986, 77). Yet, as Hamilakis’s study of the Parthenon Marbles demonstrates, objects can simultaneously operate within different value systems (Hamilakis 1999). The Parthenon Marbles, for example, function as sacred and unique cultural symbols while also serving as forms of symbolic capital within ongoing political, ethical, and museological debates. This case illustrates that the value of things is not fixed but continually renegotiated, allowing overlapping systems of meaning and exchange to coexist.

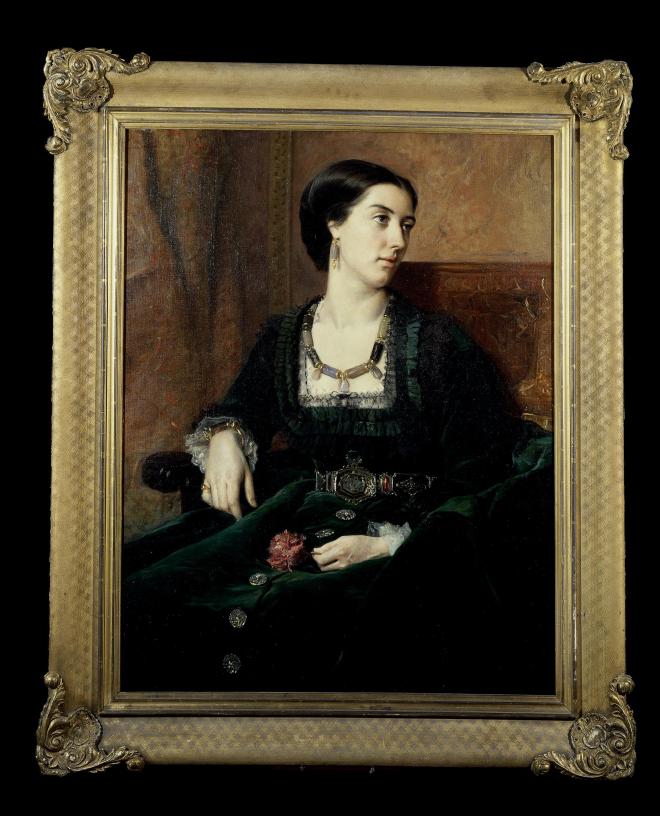

Another reason the object biography metaphor is considered inadequate is that it implies objects have distinct moments of birth and death, overlooking their continued transformations and recontextualizations. Both moments, however, present significant challenges. It is often difficult to determine the exact point at which an object comes into existence—not only because manufacturing processes can be complex and extended over time, but also because the “death” of one object may coincide with the “birth” of another. For example, in 1869 Sir Austin Henry Layard commissioned Philipps Brothers & Sons to create a jewelry set as a wedding gift for his wife, Lady Layard (née Enid Guest). The set included a necklace, a pair of earrings, and a bracelet, all made using Mesopotamian cylinder and stamp seals Layard had collected during his travels in the Middle East. These seals span a wide chronological range—from as early as 2200 BCE to the Assyrian period (see here for a complete list of the reused seals). Moreover, cylinder seals themselves were often altered and repurposed in antiquity: their iconography and inscriptions could be reworked, with details added or erased (Lassen and Jiménez 2022).

The Object Itinerary#

The object itineraries framework seeks to address the limitations of the biographical approach by offering a model that more effectively accounts for the complex entanglements of objects. An object itinerary is defined as “the routes by which things circulate in and out of places where they come to rest or are active” (Joyce 2015, 29). It encompasses not only movement within a physical space but also alteration, transformation, and intersection with other itineraries. The concept of entanglements captures the dynamic, interconnected, and non-linear relationships among people, objects, ideas, and environments—relationships that are continually shifting and evolving. Rather than viewing an object’s life as a linear progression or biography, the itinerary framework conceptualizes it as an ongoing journey of crossings, transformations, and connections. An object’s itinerary thus includes its passage through time and space, its interactions with people and other things, and the changing meanings and roles it acquires along the way. This approach traces not only where an object has been, but also how it remains entangled in present relationships.

Unlike biographies, itineraries need not be linear or bounded by a clear beginning or end; they can be open-ended, multidirectional, and composed of fragments, transformations, and intersections with other trajectories. Within this framework, being “in motion” (Joyce and Gillespie 2015) does not necessarily entail physical displacement in three-dimensional space. However, Knappett (2013, 36) observes that both the itinerary and biography metaphors often risk overemphasizing linear trajectories and overlooking periods of stasis or persistence. Object movement, he argues, is discontinuous—punctuated by pauses and stability. The object-itinerary metaphor, in particular, tends to imply constant motion, whereas artefacts do not always move continuously through time or space; many remain durable, stable, and persistent (Knappett 2013, 45).

Bibliography#

Appadurai, A. (Ed.). (1986). The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511819582

Bauer, A. A. (2019). Itinerant Objects. Annual Review of Anthropology, 48, 335–352. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-102218-011111

Hamilakis, Y. (1999). Stories from Exile: Fragments from the Cultural Biography of the Parthenon (or ’Elgin’) Marbles. World Archaeology, 31, 303–320. https://www.jstor.org/stable/125064

Joyce, R. A. (2015). Things in Motion: Itineraries of Ulua Marble Vases. In R. A. Joyce & S. D. Gillespie (Eds.), Things in Motion: Object Itineraries in Anthropological Practice (First edition, pp. 21–38). School for Advanced Research Press.

Joyce, R. A., & Gillespie, S. D. (Eds.). (2015). Things in Motion: Object Itineraries in Anthropological Practice (First edition). School for Advanced Research Press.

Knappett, C. (2013). Imprints as Punctuations of Material Itineraries. In H. P. Hahn & H. Weis (Eds.), Mobility, Meaning and Transformations of Things: Shifting Contexts of Material Culture Through Time and Space (pp. 36–49). Oxbow Books.

Kopytoff, I. (1986). The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process. In A. Appadurai (Ed.), The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective (pp. 64–92). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511819582.004

Lassen, A. W., & Jiménez, E. (2022). NBC 3171: A recarved Old Babylonian-Kassite seal. Ash-Sharq: Bulletin of the Ancient Near East, 6, 58–63.

Cite as:

Scarpa, E. (2025). Itinerant Objects. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17369334

The post featured image shows the moai at Anakena Beach, Easter Island.